Merry Christmas! To celebrate the holiday, this essay traces the origins of hemophilia B, once called “Christmas Disease,” and briefly explains how gene therapy can treat it.

I.

For centuries, physicians have noticed an unsettling pattern: a string of young boys who seem doomed to bleed. Every scrape or cut on their bodies oozed blood long after other boys had scabbed and healed. Doctors didn’t know the cause; some speculated that the bloody kids merely had “fragile blood vessels.” Others suspected that platelets — the small, disc-like cells that help form clots — were defective. A slight bump against a doorframe might cause a bruise that blackens and spreads beneath the skin. Even a bending of the knees could cause joints to fill with blood! Worse still, internal organs would rupture and hemorrhage, causing the lungs or brain to fill with blood.

Whatever the cause, families watched their children die before reaching adulthood. In the 1960s, prospects for people with this disease were grim. A 1967 study noted that of 113 patients who went untreated, most died in childhood or early adulthood, often from minor injuries that triggered uncontrolled bleeding. Only eight of these patients survived beyond 40 years.

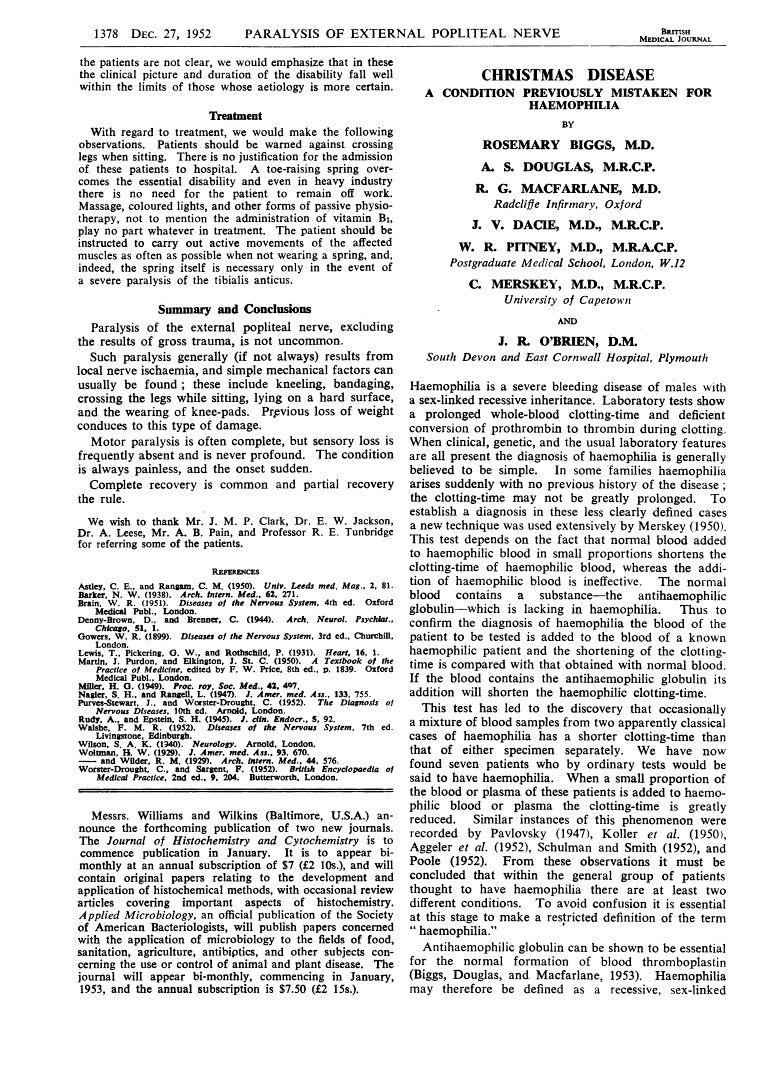

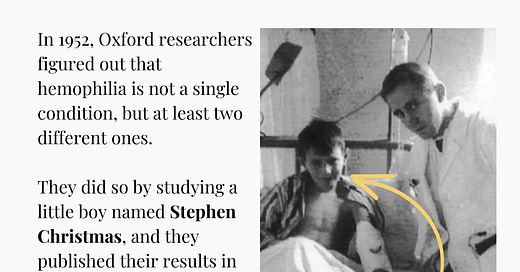

It wasn’t until the mid-20th century that researchers began to unravel, slowly, a mechanism for the disease. In 1952, researchers at Oxford University figured out that hemophilia — as the disease came to be called — was not one condition, but at least two. They reached their conclusion while studying a young boy named Stephen Christmas, and even published their findings in the Christmas issue of the British Medical Journal.

II.

Scientists have known about hemophilia since ancient times. The Babylonian Talmud forbade the circumcision of a male child if two of his brothers had already died from bleeding from the same procedure. In the 12th century, an Arab physician named Albucasis described a family in which multiple male relatives bled to death after minor injuries, according to an academic review titled The History of Hemophilia. These early authors had no way of understanding genetics, but they did suspect some kind of inherited pattern — a familial “curse,” so to speak.

The first clinical documentation of hemophilia in the “modern literature” appeared in 1803. John Conrad Otto, a physician in New York, noted the disorder among his patients; he painstakingly traced pedigrees, mapping who bled and who carried the condition. This analysis laid the foundation for understanding hemophilia as an inherited disease on the X chromosome, although the exact genetic mechanism was not yet known. Otto published his findings in an article entitled, “An Account of a Hemorrhagic Disposition Existing in Certain Families.”

Two decades later, Friedrich Hopff at the University of Zurich dug more deeply into the disease by studying families with recurring bleeding disorders and tracking which males were affected. Hopff wrote detailed case histories of men who bled spontaneously or who bled for days after a minor trauma. It was Hopff who first coined the term “hemophilia” by combining the Greek “Hemo-” (blood) and “-philia” (love or affinity).

In the 19th century, hemophilia gained widespread attention when doctors realized that Queen Victoria of England — who reigned for 63 years, from 1837 until 1901 — carried the disease. Victoria passed it to her youngest son, Leopold, who died of a brain hemorrhage at 31 in Cannes. (At the end of his life, Leopold retreated to the south of France in search of refuge from the harsh British winters.)

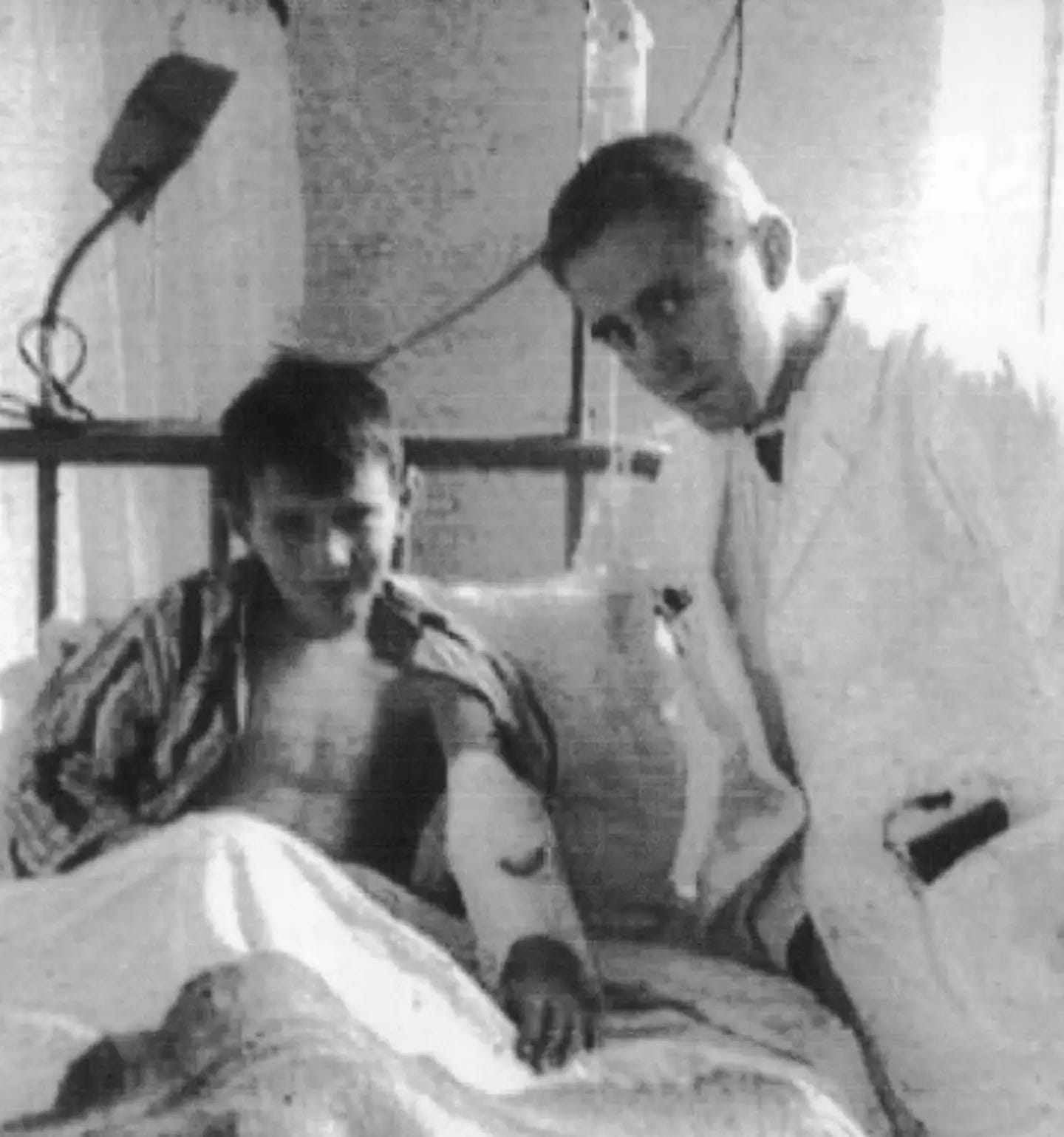

Two of Queen Victoria’s daughters, Alice and Beatrice, were also carriers. After marrying into other royal houses, they spread hemophilia into Spain, Germany, and Russia. Tsar Nicholas II’s son, Alexei, also inherited the gene through his mother, Alexandra (a granddaughter of Queen Victoria). It was Alexei’s frequent bleeding episodes that first drew Grigori Rasputin, a peasant faith healer, into the Romanov court. When Alexei died in 1918, so too did the last Russian tsesarevich, or heir apparent.

And still, nobody knew what actually caused hemophilia. But slowly, over time, researchers discovered much more. Like how a defective segment on the X chromosome prevents the body from producing a functional clotting factor. Or that the process of clot formation in healthy people involves a series of proteins called “factors,” each activating the next in a cascading sequence.

Factor IX, for example, helps convert prothrombin into thrombin, which in turn converts fibrinogen into fibrin to form a stable clot. When mutations disable factor IX, the clotting cascade stalls. Patients then bleed more, sometimes dramatically. This defect became known as hemophilia B. If the mutation affects another factor instead, called VIII, then patients are said to have hemophilia A. (There is also a third form of hemophilia, type C, that affects factor XI.)

In the early 20th century, physicians did not know there were different subtypes. They had assumed that all these bleeding problems stemmed from the same root cause: “weak blood vessels.” This assumption persisted into the 1930s.

But then, in 1936, two Harvard doctors isolated a substance from plasma that could fix the clotting defect in some people with hemophilia. They named this substance “antihemophilic globulin,” but did not know why the substance helped blood clot in some cases, yet not in others.

An answer to their question would not appear until 1947, when an Argentinian physician named Alfredo Pavlosky mixed blood from two separate hemophilia patients and found, oddly, that the blood clotted quickly. One of those patients had hemophilia A, and the other had hemophilia B. Neither realized it at the time, but this observation showed that each patient lacked a distinct factor. One patient’s factor VIII could complement the other patient’s factor IX deficiency, and vice versa. Researchers slowly began to recognize that they were dealing with separate disorders.

The defining moment in hemophilia B’s story, though, came in 1952. That’s the year Oxford scientists first described a five-year-old boy, named Stephen Christmas, who had frequent, uncontrollable bleeding since he was 20 months old. When the doctors mixed Christmas’ blood with blood from hemophilia A patients, they noted normal clotting; much like Pavlosky had five years earlier. The scientists therefore concluded that Stephen Christmas did not lack “antihemophilic globulin” (now called factor VIII).

Unlike Pavlosky, though, the Oxford team took their experiments much further and showed, for the first time, that Christmas was missing a different protein, which they dubbed the Christmas Factor (factor IX). Their findings were published in the British Medical Journal’s Christmas issue and the disease was named, fittingly, “Christmas Disease.”

The Oxford team used clever blood-mixing experiments to make their discovery. They took small samples of blood plasma from different patients and observed what happened when they were combined. If two samples improved clotting times when mixed, it suggested that each plasma had at least some clotting element the other lacked. For instance, mixing patient #2’s blood with patient #4’s blood yielded faster clotting times, indicating that each person was deficient in a different factor. In contrast, mixing certain pairs that both lacked the same factor did not produce any improvement in clotting. This approach ruled out the possibility that Christmas Disease was simply hemophilia A by another name. Over time, the disease was renamed to hemophilia B.

III.

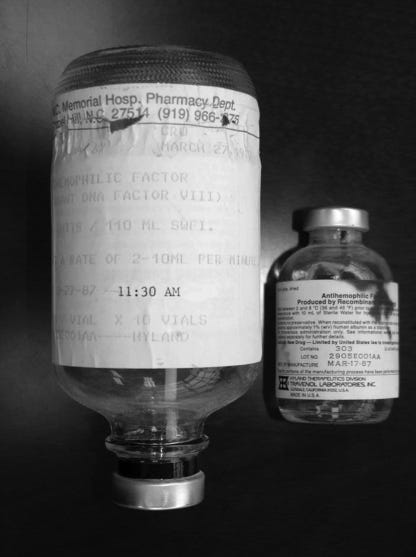

Efficacious treatments for hemophilia did not appear for another decade after the Christmas paper. In 1964, a Stanford scientist named Judith Graham Pool discovered that the slushy precipitate left after partially thawing plasma (called the cryoprecipitate) contained a high concentration of factor VIII. This discovery meant that blood banks could collect and store large amounts of clotting factors in relatively small volumes.

Patients with hemophilia A — a factor VIII deficiency — could now receive fewer, more potent infusions to control or even preempt bleeding episodes. This was great news, of course, but it did not help hemophilia B directly because factor IX was still missing from the cryoprecipitates. Still, hemophilia A affects about six-times more people than hemophilia B (1:5,000 births, compared to about 1:30,000 births) and the idea of separating and concentrating specific clotting factors set the stage for future treatments.

The next leap came in the 1970s, when researchers developed freeze-dried concentrates containing both factor VIII and factor IX. These concentrates could be stored easily and administered at home, which allowed patients to treat themselves as soon as bleeding began. Orthopedic surgeries also became much safer, giving patients a chance to correct damage that had already accumulated.

In Sweden, doctors like Inge Marie Nilsson and Ake Ahlberg went even further: they pioneered prophylactic treatment, giving factor VIII to hemophiliacs on a regular schedule rather than waiting for bleeds. The same principle applied to factor IX for hemophilia B patients. This approach transformed hemophilia from a life-threatening disorder into a manageable, yet chronic, condition.

There is a tragic sidenote in this tale, though. Before 1985, many plasma-derived concentrates were unknowingly contaminated with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis viruses. A devastating number of hemophilia patients contracted these conditions. It is estimated that 4,000 of the 10,000 hemophiliacs then thought to be living in the U.S. died from AIDS.

Today, hemophilia has morphed from a chronic condition into a curable one. Lasting genetic fixes are now available. Rather than requiring frequent or even weekly infusions of factor IX, patients can get a one-time dose of a gene therapy — such as Hemgenix, a gene therapy approved by the FDA in 2022 — that prompts their own cells to make factor IX.

Hemgenix is a one-time infusion for hemophilia B. It works like this: First, a healthy gene encoding the factor IX gene is inserted into an adeno-associated virus, or AAV. This virus is then infused into the bloodstream (this takes an hour or two), where it travels to the liver, gloms onto cells, and delivers its genetic payload. The AAVs deliver the healthy gene into liver cells. The gene integrates into the cells' DNA, instructing them to make functional copies of factor IX. After getting Hemgenix, 96% of participants stop using their normal medication.

The Hemgenix clinical trials measured the annualized bleeding rate before and after gene therapy. During the lead-in period, patients had about 4.1 bleeds per year. In months 7 to 18 after treatment, that average dropped to 1.9 bleeds per year. In other words, patients receiving Hemgenix bled less than half as often after receiving the gene therapy compared to before. The researchers also measured how much functional factor IX the patients’ blood contained over 24 months. Their factor IX levels hovered around 36–41% of normal. That range is typically enough to cause blood clotting, making severe bleed outs much less likely.

In the United Kingdom, the National Health Service will pay about 2.6 million pounds per patient for Hemgenix. This price may seem high, but it’s likely far lower than the costs required to give those patients factor replacement medicines over several decades of their lives.

It’s incredible to me that only one hundred years ago, families watched helplessly as children with “weak blood vessels” bled and died from small bumps. And that now, we have a gene therapy that corrects the disorder and makes hemophilia liveable for the first time in human history.

So this Christmas, I’m grateful for biotechnology. Although often tied to scary things like “bioweapons” — especially by those outside of biology — my experience is that biotechnology is far more often used as a force for good. Christmas disease is just one example of that. In 2025, I’m hopeful that we’ll see much more progress on AAV engineering (using AI and other tools!) to make gene therapies safer and more precise, and less likely to cause severe immune reactions. If we figure this out, gene therapies could be used to cure many diseases that were once considered little more than death sentences.

Merry Christmas,

— Niko McCarty

![r/HistoryPorn - Tsarevich Alexei Nikolaevich of Russia during a mudbath treatment (probably a naturopathic attempt to treat his hemophilia) at Livadia, Crimea, Autumn 1913. In the background stands Alexei's sailor nanny Andrei Derevenko, Dr. Botkin holds the left hand of the Tsarevich. [1024x1010] r/HistoryPorn - Tsarevich Alexei Nikolaevich of Russia during a mudbath treatment (probably a naturopathic attempt to treat his hemophilia) at Livadia, Crimea, Autumn 1913. In the background stands Alexei's sailor nanny Andrei Derevenko, Dr. Botkin holds the left hand of the Tsarevich. [1024x1010]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F4067cdf8-93c1-4712-a205-e96e89306a74_640x631.jpeg)