Antivenom Renaissance

Two new papers use AI tools to explore antivenoms in different ways.

There are two new “venom AI” papers out, and both are interesting for different reasons.

The first paper, published in Nature and already covered by Derek Lowe in his blog, uses RFdiffusion — a computational protein design tool — to make proteins capable of neutralizing a wide range of lethal snake toxins.

The second paper, a preprint posted on bioRxiv, does this almost in reverse; instead of using AI to discover proteins that neutralize venoms, it instead uses AI to sift through millions of venom proteins to find those capable of killing drug-resistant bacteria. (Many venom proteins have evolved over time to be antimicrobial, for reasons that nobody seems to fully understand; perhaps it’s to keep bacteria from moving into a snake’s venom-producing glands. If one screens enough venomous proteins, then, the hypothesis is that we’ll find useful proteins to treat diseases, similar to how GLP-1 drugs came from Gila monsters...)

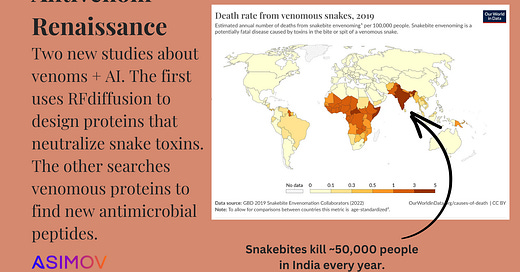

The first paper, published by the Baker lab at the University of Washington, could help resolve a major problem in global health; namely, the fact that snakebites kill about 50,000 people every year in India alone, and existing antivenoms need cold-chain storage and are still made by bleeding large animals in a ridiculously tedious process that hasn’t changed much in a century. (In Australia, only about two people die from snakebites each year, despite the country having far more venomous snakes than India.)

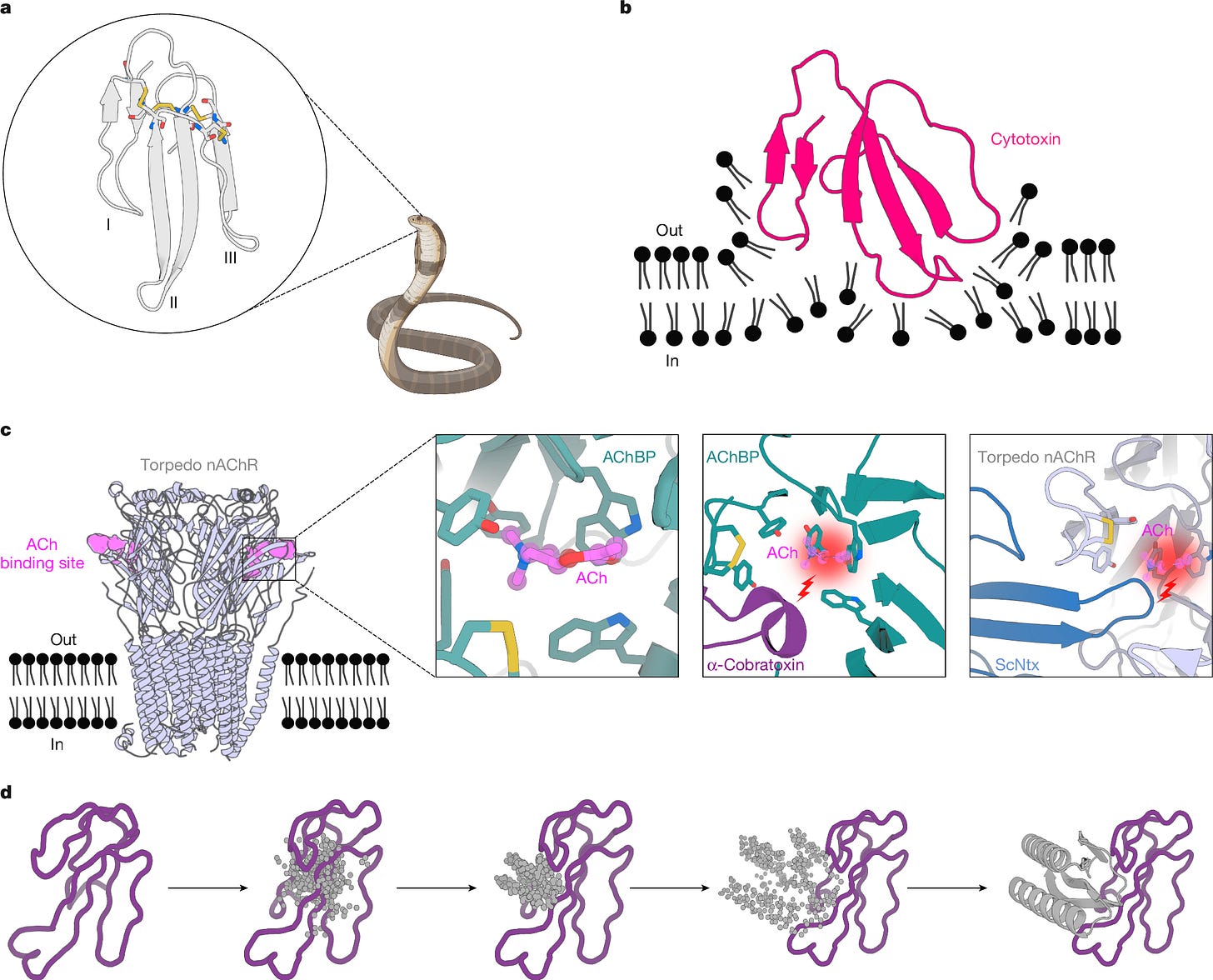

The Baker group’s designed protein binds to three-finger toxins, a family of snake toxins that include α-neurotoxins and cytotoxins. It is also designed to be quite stable at higher temperatures, so that its transport doesn’t require refrigeration. The authors used RFdiffusion to build proteins that match up with the toxin’s shape, grab onto the molecule, and then physically block the toxins from latching onto neuromuscular targets.

Just because someone makes a better antivenom, though, doesn’t mean it’ll scale. Lowe notes as much in his column (bolding my own):

In vivo experiments in mice showed that the anti-neurotoxin candidates did indeed protect mice from lethal challenges of their protein partners, both when given simultaneously or when given fifteen minutes after toxin injection. These were in tenfold excess to the toxin dose, and given the rather low volumes that snakes deliver that seems doable for human therapy. The mice themselves showed no acute ill effects during or after the treatments, but if these get moved on towards humans the usual warnings for protein therapies apply: you'll have to make sure that you don't set off unwanted immune responses to the drugs themselves, as well as looking at metabolic stability and so on.

And even if this protein does reach clinical trials, it may not even cure snakebites on its own. Lowe continues:

There are other classes of nasty ingredients in snake venoms, with phospholipase enzymes near the top of the list. But these same techniques might be expected to deliver neutralizing proteins against these other targets, given the money, effort, and time, and the eventual therapy would surely be a cocktail of different proteins, ready to inject.

Now let’s move on to the bioRxiv preprint, which I haven’t seen covered in blogs elsewhere.

This study, by a group of UPenn researchers who have already done a lot of pioneering work on antibiotic discovery, uses venom and AI tools to go after a very different problem — namely, antibiotic-resistant microbes. Their hypothesis was basically that venoms are “a remarkably diverse reservoir of bioactive molecules,” according to the preprint, that could possibly offer “an underexploited source” of useful medicines.

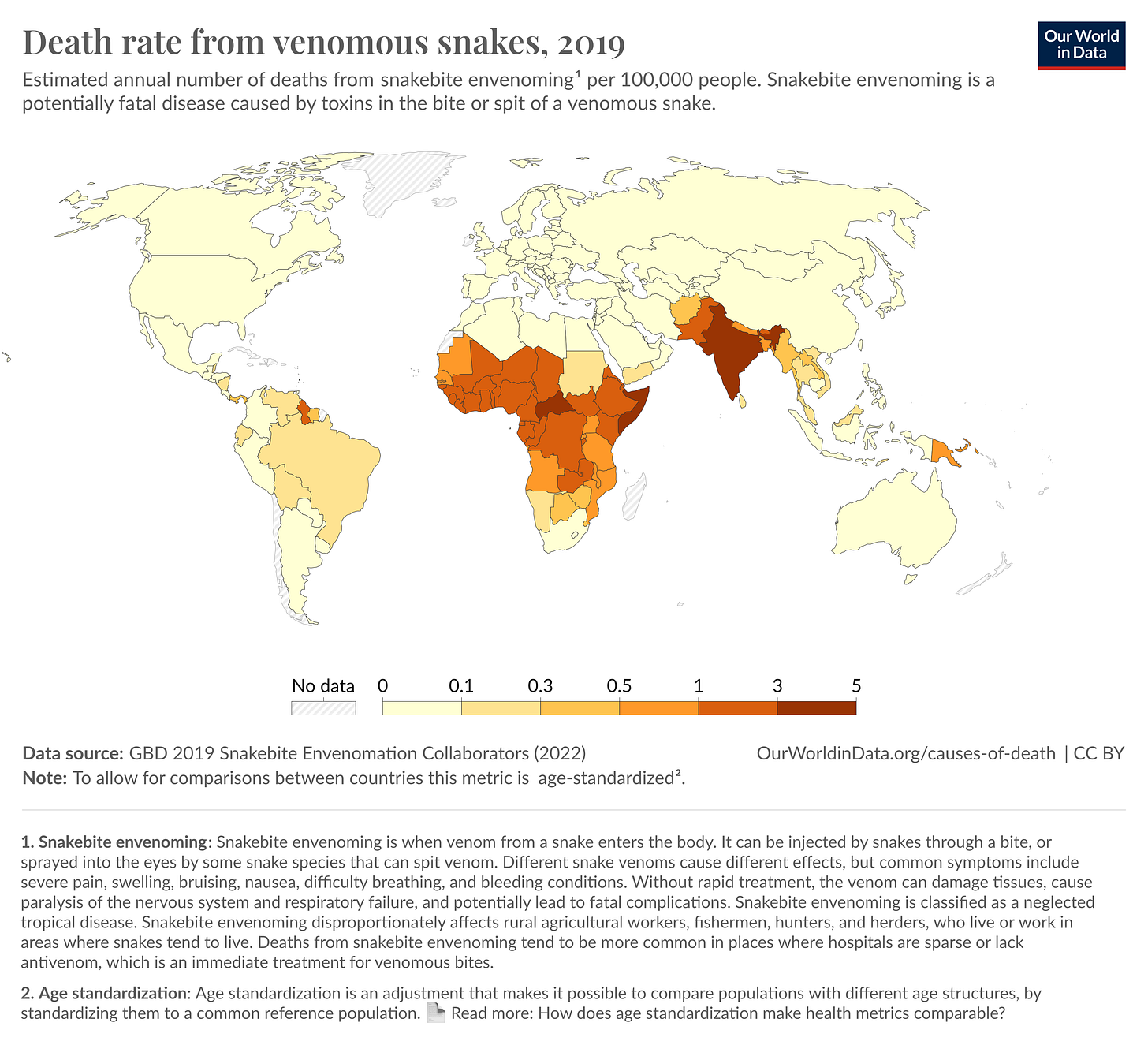

So here’s what they did. First, the researchers sifted through four different “venom databases” to scrape 40 million venom-encrypted peptides, or small proteins present in snake venoms. Next, they used a deep learning model called APEX (first published in June 2024) to predict which peptides had a low MIC, or minimum inhibitory concentration, against microbes. (In other words, this deep learning model looks at the structure of a peptide and tries to predict its function, or how effectively it will kill microbes.) The authors then removed any peptides with similar sequences to known antimicrobials, and ended up with a list of just 386 candidates — peptides that look nothing like existing medicines and that were predicted to have potent, antimicrobial properties.

In a follow-up experiment, the UPenn researchers synthesized 58 of the candidates in the laboratory and then tested their activities against various pathogens. About 91 percent of the candidates “exhibited activity against at least one pathogenic strain,” according to the study, usually by depolarizing the microbes’ cell membranes. (This means that the affected cells are no longer able to move ions across the membrane and, thus, make energy. They slowly starve to death, basically.)

In mice infected with A. baumannii — a pathogen commonly involved in hospital-acquired infections — three of the discovered peptides showed “promising activity” and saved the mice. One of these peptides came from a scorpion, a second from a cone snail, and the third from a wolf spider.

Putting these papers together, then, we have two case studies at opposite ends of the “venom use” spectrum: toxins as a source of antibiotic scaffolds, and toxins as targets for newly designed mini-proteins. In both cases, the recurring theme is that AI models can do things that conventional guesswork or brute-force screening cannot solve quickly.

There’s plenty more work to do in terms of scaling “AI discoveries” into the real-world, and most of the bottlenecks have to do with the slowness of the real-world itself. Clinical trials still take a long time and cost a ton of money, patients still need to be recruited, and so on. But at least the preclinical bottlenecks are slowly falling away.

Thanks for reading,

— Niko

References:

Derek Lowe. “Snake Antivenoms, Computed.” In the Pipeline. Link

Saloni Dattani. “How many people die from snakebites?” Scientific Discovery. Link

Torres S.V. et al. “De novo designed proteins neutralize lethal snake venom toxins.” Nature. Link

Guan C. et al. “Venomics AI: a computational exploration of global venoms for

antibiotic discovery.” bioRxiv. Link

Very interesting!

Have you been following the development of the small molecule venom inhibitors? When we spent 18mo in south america and Africa, we got a molecules maker to synthesise marimastat because of all the problems with antivenom.

Preclin Nature paper here:"A therapeutic combination of two small molecule toxin inhibitors provides broad preclinical efficacy against viper snakebite", and much more since.