Arithmetic is a superpower. Or, as Dynomight has written, a “world-modeling technology.” It is one of the first things we learn in school, and yet few seem to use it in everyday life to make predictions about the world.

Physicists use back-of-the-envelope arithmetic all the time, though. Enrico Fermi famously used it to estimate the energy released during the Trinity atomic bomb test. Standing ten miles away, he wrote that:

About forty seconds after the explosion the air blast reached me, I tried to estimate its strength by dropping from about six feet small pieces of paper before, during and after the passage of the blast wave. Since, at the time, there was no wind, I could observe very distinctly and actually measure the displacement of the pieces of paper that were in the process of falling while the blast was passing. The shift was about 2.5 metres, which, at the time, I estimated to correspond to a blast that would be produced by ten thousand tons of TNT.

I don’t often meet biologists who use similar estimates to test their assumptions, even though they stand to benefit just as much as physicists. In Fast Biology, I gave an anecdote about some Caltech researchers who were trying to figure out the rate-limiting factor for bacterial growth — specifically, the “thing” that limits a cell’s division rate. They found the answer (ribosome biosynthesis) using simple arithmetic, scribbled on a sheet of paper. No complicated experiments were required.

I’d like more biologists to use simple arithmetic to check their ideas prior to running experiments. Similarly, I hope more people outside biology will enter the field and contribute. To encourage this, I’m launching a new blog series called Order-of-Magnitude Thinking. Every few weeks, I’ll pose a question and walk through the steps I take to arrive at an answer using arithmetic. I hope you’ll follow along and try these calculations yourself. Over time, I think you’ll become adept at developing biological intuitions, doing sanity checks on experiments, and so on.

Let’s start with a basic question: How long does it take E. coli to turn one average-sized gene into one protein?

Before answering, let’s review some molecular biology. When I say “turn,” I really mean transcribe DNA into messenger RNA (mRNA), and then translate that mRNA into protein. We can think of a gene, in this case, as a stretch of DNA that contains all the instructions needed to build that protein. Three mRNA letters are called a “codon” and encode one amino acid — the building blocks of proteins. Thus, a gene’s length in nucleotides is at least three times longer than the protein it encodes.

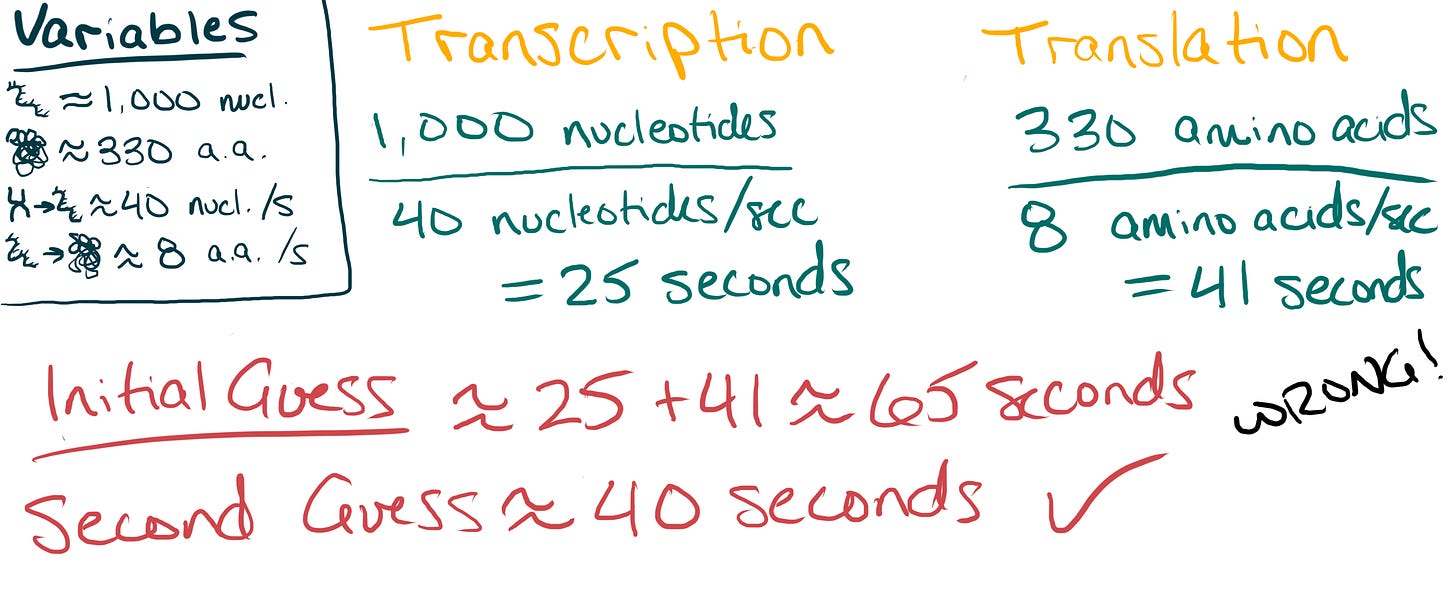

Now we’re ready to move forward. The first step is to break down the question and collect our variables. We’ll need to know the size of an average gene in E. coli, the size of a protein encoded by that gene, the transcription rate (the number of DNA “letters” converted to mRNA per second) and the translation rate (how many amino acids are added to a protein per second).

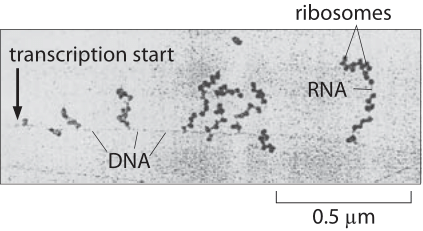

If this question was about mammalian cells, we’d also need to account for the time it takes mRNA to move from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. But E. coli cells lack a nucleus, so we can ignore this step; their genome is mixed in with everything else, meaning that ribosomes can kick off translation as soon as a mRNA appears.

I use the BioNumbers database to look up variables. Searching “average gene length E. coli” yields an answer of about 330 amino acids. Recall that each amino acid is encoded by three nucleotides, so let’s assume that an average E. coli gene has about 1,000 nucleotides.

What about transcription and translation rates? At 37°C (a standard temperature for E. coli growth), the transcription rate is about 40 nucleotides per second. A typical translation rate is 8 amino acids per second.

Great. Now that we’ve got our numbers, we can carry on with the calculation.

First, we calculate the transcription time — the number of seconds it takes to convert our average-sized gene into mRNA. This is 1,000 nucleotides divided by 40 nucleotides per second, or 25 seconds.

Next, we calculate the translation time — the time required for ribosomes to convert the mRNA into a protein. This is 330 amino acids divided by 8 amino acids per second, or about 41 seconds.

At first glance, we might assume that the total time to make a protein is the sum of these two values: 25 seconds + 41 seconds = 66 seconds, or 1 minute and 6 seconds. But because E. coli lacks a nucleus, transcription and translation happen at the same time. Translation kicks off as soon as the mRNA starts forming. In other words, the creation of proteins in E. coli is bottlenecked by the speed of translation. Therefore, I’d estimate that it only takes about 40 seconds to make one protein from a gene.

Keep in mind that this estimate involves several assumptions! For instance, we’re assuming that proteins fold immediately, even though some take several minutes to adopt their final structure. We’re also assuming that transcription begins immediately, even though the cell may have to wait several seconds for the correct enzyme to latch onto the correct gene. Many biological processes are limited by diffusion — the time it takes for molecules to encounter each other — and this is an issue I’ll return to in future estimates.

In any case, the goal of order-of-magnitude estimates is to get within a factor of ten of the underlying reality. It’s okay to round numbers up or down, or to factor in some of your assumptions, to make your final estimate. You’ll develop an intuition for how to do this effectively over time. But for this question, I think it’s safe to say that it takes “a minute or so” to make a protein from a gene in E. coli.

Until next time,

Niko McCarty

Hi Niko,

I am very glad you're doing this series. I have often been preoccupied by estimating the scale of biology within an order of magnitude because I think it's an interesting way of conveying to people (especially non-biology nerds) what future synthetic biology or ecology might be able to tap into. I think biology will be a key to becoming a Type 1 civilization.

Viroids, although not technically alive, are 300 nt long, so that's like 300 nm, Pando, the aspen grove in Utah, appears to be the largest organism, and that's at least .72 km on a side, so that's like 9 orders of magnitude. But you could also include biomes so maybe biology exists at more than 12 orders of magnitude.

Anyway, I'm interested to see the directions this series goes in.

Thank you for the interesting blog. Is there any reference for humans,average size of a gene, transcription rate and translation rate?