Quick Announcement: This blog has had a rebrand. I’ve changed the name from “Atoms Only” to “The New Biology,” simply because I think this new name better captures the sentiment of what I’m writing about. Also, this blog is now part of Asimov. What that means, basically, is that I’m still going to write about whatever I want (like this post), but about once a month I’ll also send out an article about bioengineering experiments going on inside the company. Thanks for reading.

When people think of “biotech” — myself included — they tend to picture GLP-1s and gene therapies. But biotech is much broader than just medicine; it’s also pushing forward a renaissance in the egg industry.

Eggs aren’t usually top of mind for me. I toss a carton in my grocery cart now and then, but rarely think about how those eggs landed on the shelf in the first place. Perhaps I should. Every year, the global egg industry kills around six billion male chicks shortly after they hatch. Why? Because male birds, bred from “layer” lines, don’t make eggs and don’t pack on enough meat to be profitable. Hence, they’re thrown into a blender.

Fortunately, scientists have figured out how to determine a chicken’s sex before it hatches. These technologies are called in ovo sexing. Using hyperspectral cameras or PCR, they can be used to figure out which eggs will hatch male vs. female. With widespread adoption, in ovo sexing could spare billions of chicks from the blender. Alas, these technologies weren’t available at all in the U.S. … until last month. Hardly anyone in the mainstream biotech community seems to know about what’s going on in this sector but, in my view, it’s among the most underrated and important stories of today.

In ovo sexing has been available in Europe for years. Germany banned chick culling in 2022. In response, hatcheries were initially forced to keep male chicks alive and raise them for meat — “a practice that was costly and unsustainable,” according to Innovate Animal Ag. (Again, so-called “layer” chickens just don’t produce much meat. Broiler chickens, on the other hand, are specially bred to grow quickly; they “can grow to be over four times the weight of a natural chicken in only 6-7 weeks,” according to an article in Asimov Press.)

Sensing an opportunity, companies launched in ovo sexing technologies in Europe so hatcheries could screen out male eggs before they hatched. If eggs are destroyed by day 12 of development, the embryo feels no pain. Thanks to this shift, about 78.4 million of Europe’s 389 million hens — or about 20 percent — came from in ovo sexed eggs last year, according to data from Innovate Animal Ag.

But only two in ovo sexing methods have reached commercial scale so far. As Robert Yaman, CEO of Innovate Animal Ag, previously wrote for Asimov Press:

The first of these approaches utilizes imaging technologies like MRI or hyperspectral imaging to look “through” the shell of the egg to determine the sex of the embryo inside. The second approach involves taking a small fluid sample from inside the egg, and then running PCR to identify the sex chromosomes, or using mass spectrometry to locate a sex-specific hormone…

…Other approaches are in development and have not yet been commercially deployed. Some technologies can “smell” a chick’s sex by analyzing volatile compounds excreted through the eggshell. Another approach uses gene editing so that male eggs have a genetic marker that allows their development to be halted by a simple trigger, such as a blue light. Unlike humans, the sex of a chicken is determined by the chromosomal contribution of its mother. By only modifying the sex chromosome of the female parent line that yields male chicks, the female chicks end up without the gene edit. This means that the eggs they lay do not need to be labeled as “gene-edited” for consumers.

As Europe rolls out these technologies, most American consumers still have no idea that chick culling is even a thing. In one poll, only 11 percent of Americans knew about chick culling; once informed, a majority opposed it. Fortunately, in ovo sexing technologies have finally arrived in the U.S.

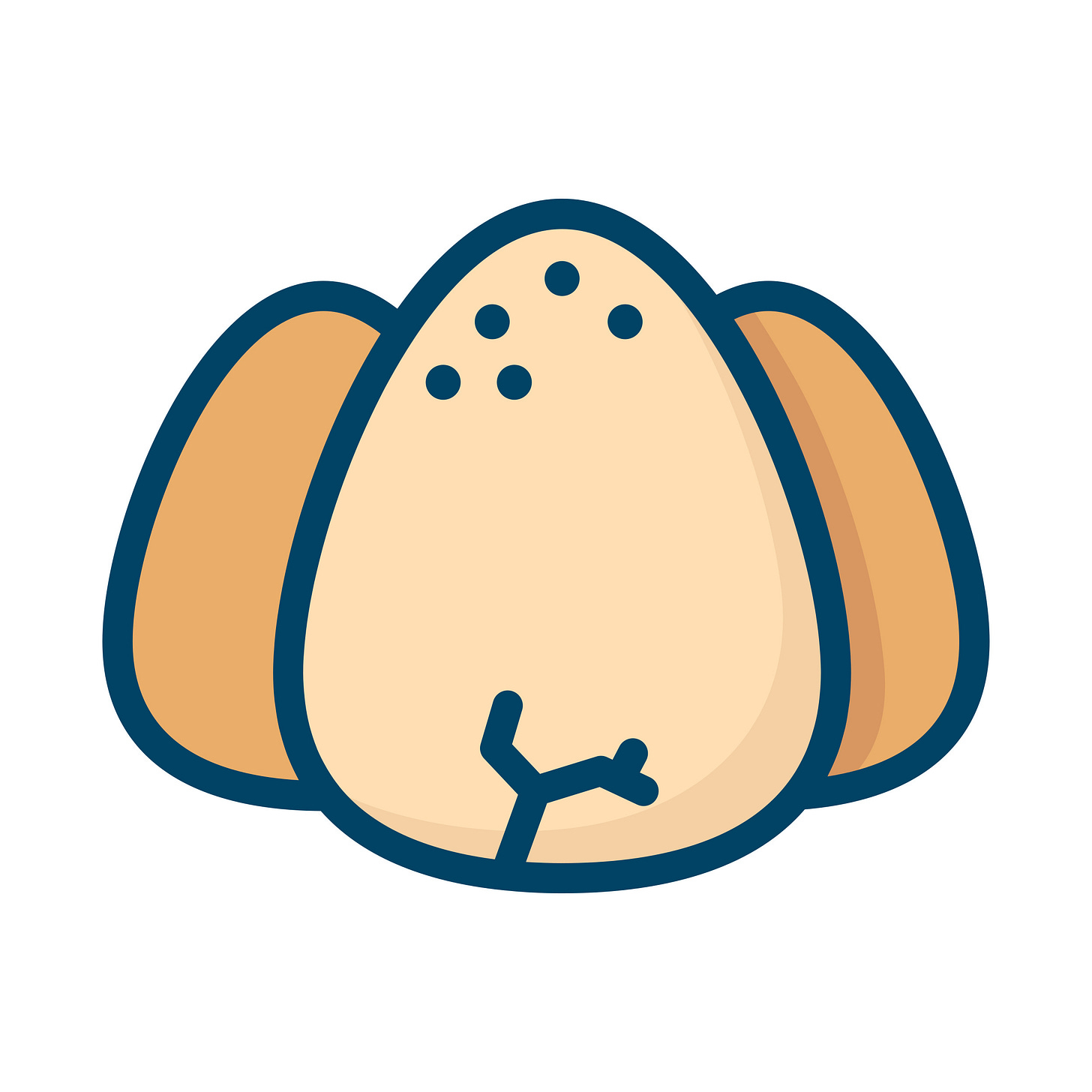

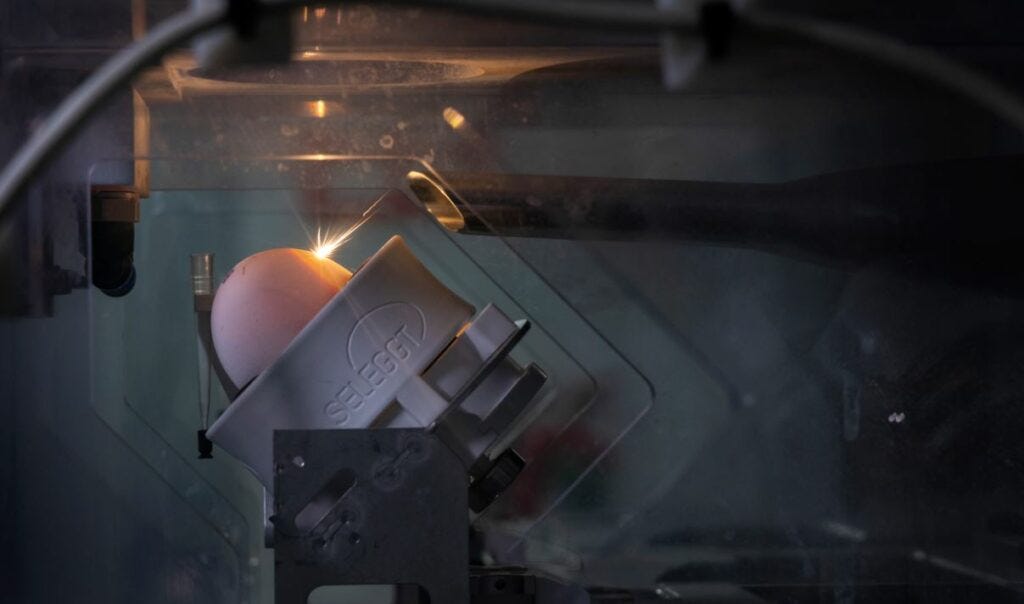

Three U.S. egg companies — Egg Innovations, Kipster, and NestFresh — have announced plans to adopt in ovo sexing technology. In late 2024, Agri-Advanced Technologies also rolled out a machine called “Cheggy” to hatcheries in Iowa and Texas. Cheggy can scan 25,000 eggs per hour and figure out the sex of embryos inside using hyperspectral imaging. The machine is able to “see” the color of down feathers forming beneath the shell. (Brown-egg chicken breeds typically have differently colored feathers for males and females, but this doesn’t work on white eggs.) Hyperspectral imaging is great because it’s non-invasive; the eggs don’t need to be cracked or poked at all. If the machine detects a female embryo, it sends it back to the incubator. Male eggs are destroyed and turned into protein for pet food.

Also, in December, Respeggt announced that by February 2025, it will roll out its own in ovo sexing tech at a massive Nebraska hatchery, with a capacity to serve 10 percent of the entire U.S. layer market. Respeggt’s technology relies on PCR, so it works for both white and brown eggs.

In Europe, in-ovo-sexed eggs cost only about one to three euro cents more each. That’s a tiny bump, and I’d gladly pay extra just for the mental solitude of knowing that farmers didn’t have to kill any male chicks to produce them. But I am not most consumers; eggs are one of the most price-sensitive grocery items. When people talk about inflation, they usually talk about the price of bread, milk, and eggs!

Fortunately, a Nielsen survey found that 71 percent of American egg buyers say they’d pay more for in-ovo-sexed eggs. We’ll see what happens, though, as these eggs get rolled out to grocery stores (likely by mid-2025). Consumer reactions will be super important here because the U.S. government doesn’t mandate whether or not hatcheries kill baby chicks. The survival of these technologies will literally be determined by whether or not people buy the eggs.

Finally, I just want to say that few (if any) people have been pushing for this harder than Innovate Animal Ag. They didn’t pay me to say that, either; they don’t even know I’m writing this article! But they’re the ones dropping all these reports and data about chick culling, commissioning surveys to figure out price points, and pushing for new certifications to coax consumer buy-in.

So yeah, we often celebrate biotech’s potential — gene editing, advanced vaccines, cultivated meat — but in ovo sexing is already improving the egg industry at scale. It flies under the radar, but at least now you know the story.