Gregor Mendel Killed Preformationism

In the 19th-century, many biologists thought that humans came "fully-formed" inside the sperm or egg.

Imagine you are a 19th-century scientist, specifically a botanist in 1850.

The word “genetics” will not be coined for another 50 years. Nobody has yet isolated DNA (Friedrich Miescher will not do so until 1869, by grinding up pus from soldiers’ bandages), and Watson and Crick will not publish their DNA structure for another century. Nobody knows that germs cause disease; Louis Pasteur will not propose that idea until 1861. It’s a wild time to be alive, and many widely accepted beliefs, which seem totally reasonable on their face, will later turn out to be false.

So it was with preformationism, the notion that organisms exist fully formed inside an egg or sperm. In the mid-19th century, many botanists believed that pollen carried miniature, fully formed plants (and that each plant carried all future generations within it, like Russian nesting dolls). They claimed that the ovule merely served as a vessel to nourish these plants, contributing no information of its own.

Some evidence contradicted this theory, but none of it was compelling or quantitative enough to dissuade the preformationists. Until, that is, Gregor Mendel — the same friar who uncovered the “laws of inheritance” — came along and debunked it all using the common garden pea.

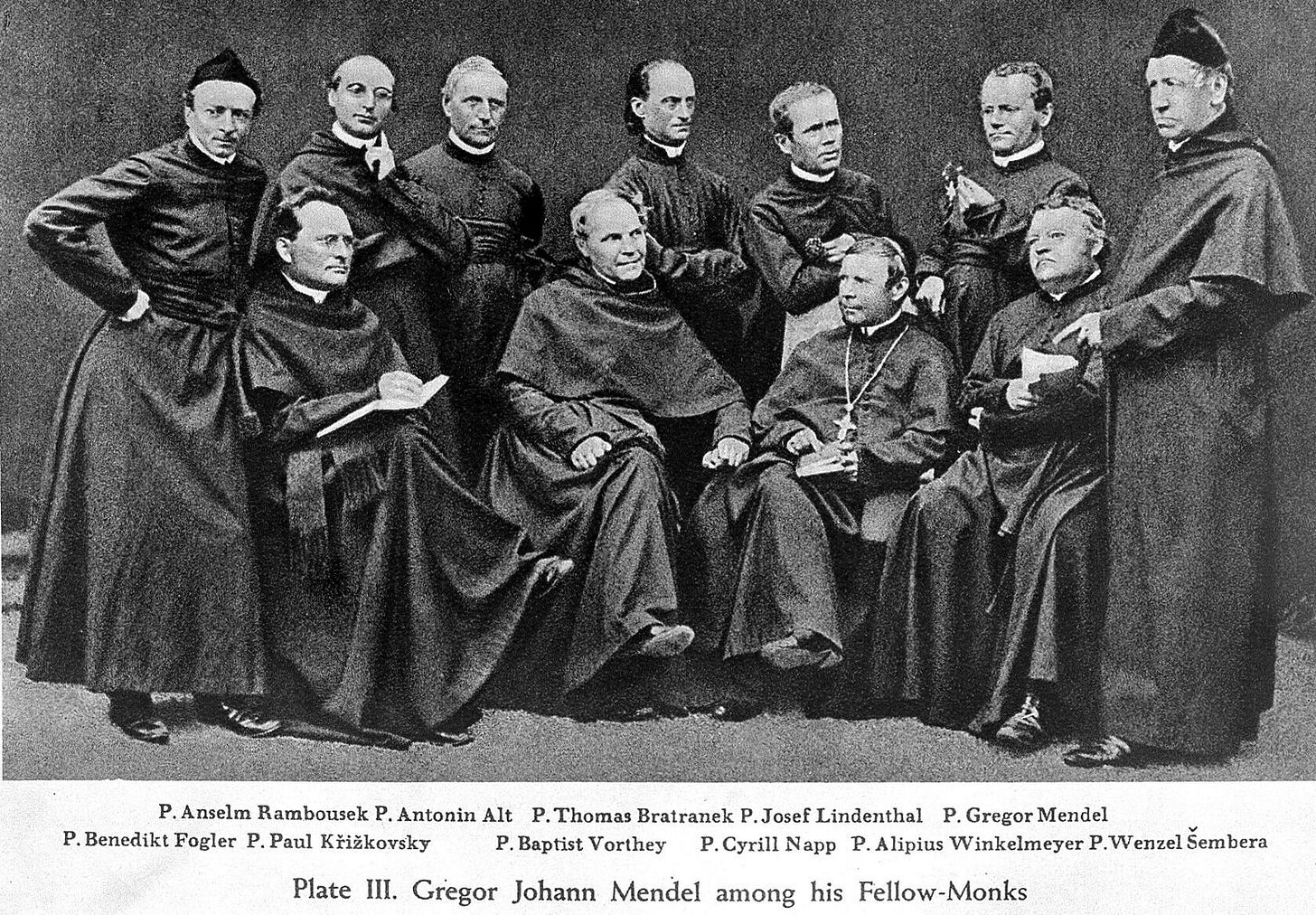

The story goes like this: In 1851, Mendel traveled to Vienna to begin his university education. While there, he studied under influential professors who shaped his views on inheritance, evolution, and mathematics. Andreas von Ettinghausen introduced Mendel to combinatorics, a branch of mathematics focused on counting. Mendel would later use this skill to analyze his pea-breeding experiments at a time when few botanists took a quantitative approach to their work. Christian Doppler (of Doppler Effect fame) taught Mendel experimental methods (but apparently did not think highly of Mendel’s math skills.)

More importantly, Mendel studied plant biology under Franz Unger, a brilliant scientist who had already formulated his own ideas on evolution well before Darwin published On the Origin of Species in 1859. “Unger attempted to link modern plants with those in the fossil record to portray an unbroken hereditary and evolutionary tree,” writes Daniel J. Fairbanks in Gregor Mendel: His Life and Legacy, “branching from the ancient past to the present.”

Mendel greatly respected Unger, who was then locked in a fierce dispute with Eduard Fenzl. Fenzl, another Viennese botanist, argued that heredity was purely paternal, with the female parent acting only as a “nurse” to the pollen, according to Fairbanks in Demystifying the Mythical Mendel. Unger disagreed, insisting that heredity flowed from both parents. In other words, Unger believed sperm (or pollen) and egg (or ovule) contributed equally to the offspring — directly challenging preformationism.

Mendel returned to the Brünn monastery in 1853 and began his famed pea experiments. He likely started them not to uncover the “laws of inheritance” but to see if Unger’s claim was correct.

Mendel spent two years ensuring that his peas were true breeding before beginning his crosses. A true-breeding plant, when self-pollinated, produces identical offspring. For example, a true-breeding yellow-seeded plant always yields yellow-seeded offspring. Mendel allowed his plants to self-fertilize for several generations and then selected only those that consistently showed stable, uniform traits.

He chose 22 true-breeding varieties as parents and later narrowed this down to seven varieties with easily distinguishable traits — seed color, seed shape, plant height, and so forth — that anyone could see with the naked eye.

Each of Mendel’s crosses demanded painstaking care because pea flowers are small and delicate. To prevent self-fertilization, he removed the anthers with tweezers, effectively “castrating” the plant so it produced no pollen. Pea plants normally self-fertilize because each flower has both male and female organs. After removing the anthers, Mendel could transfer pollen from a chosen “father” plant to the emasculated “mother” plant’s stigma without risking accidental pollination by wind or insects. (You can watch this technique on YouTube.)

This process is manageable for a few plants, but Mendel repeated it about 300 times over nearly a decade. He knew he would need thousands of plants to observe the clear mathematical patterns that would later emerge. He started his experiments in 1856 with four of the seven character pairs: seed shape, seed color, plant height, and seed coat color. By the fall of 1856, he had results for seed shape and color. For seed color, Mendel crossed true-breeding yellow-seeded plants (homozygous dominant, BB) with true-breeding green-seeded plants (homozygous recessive, bb).

All the first-generation offspring had yellow seeds because the yellow allele is dominant. They were all heterozygous (Bb). Then Mendel let these offspring self-pollinate. Among their second-generation offspring, 75 percent had yellow seeds while 25 percent had green seeds. Thus, the recessive green allele reappeared in the second generation.

But one brilliant aspect of Mendel’s experiment often goes unmentioned: He performed his crosses in both directions. He would transfer pollen from a green-seeded plant to a yellow-seeded plant’s stigma and then reverse the cross, using pollen from a yellow-seeded plant on a green-seeded plant’s stigma.

No matter which direction he did the cross, Mendel got offspring with the same ratios of traits. In doing this, Mendel provided the first compelling numerical evidence that both parents contribute genetic information equally to their offspring.

We take this idea for granted today only because Mendel made it obvious! In his 1866 manuscript, Mendel wrote:

With Pisum [pea] it is shown without doubt that there must be a complete union of the elements of both fertilizing cells for the formation of the new embryo. How could one otherwise explain that among the progeny of hybrids both original forms reappear in equal number and with all these peculiarities? If the influence of the germ cell on the pollen cell were only external, if it were given only the role of a nurse, then the result of every artificial fertilization could be only that the developed hybrid was exclusively like the pollen plant or was very similar to it. In no manner have experiments until now confirmed that.

I encountered this story recently while researching a long-form article on Gregor Mendel’s life for

(which will be published this Sunday). After reading two books and dozens of academic reviews on Mendel’s work, I found that much of the friar’s efforts were missing from my university genetics courses — this story among them.