There’s a new paper out in PNAS that hints at some intriguing synthetic biology applications. Researchers at the University of Rochester introduced a sea sponge gene into Escherichia coli, giving the bacteria a translucent, silica-based coating. This biosilica shell transforms the cells into tiny microlenses that focus beams of light.

Here’s an excerpt from the paper (paywalled):

Remarkably, the polysilicate-encapsulated bacteria focus light into intense nanojets that shine nearly an order of magnitude brighter than unmodified bacteria. Polysilicate-encapsulated bacteria remain metabolically active for up to four months, potentially enabling them to sense and respond to stimuli over time. Our data show that synthetic biology can produce inexpensive and durable photonic components with unique optical properties.

Typically, microlenses are just tiny spheres, a few micrometers across, fabricated in cleanrooms with harsh chemicals. They appear in photodetectors and camera sensor arrays. Engineered microbes can’t match the precision of these fabricated microlenses, but they offer a major advantage: you can make them at room temperature and neutral pH in a flask of liquid. (And the cells reproduce themselves “for free”!)

Notably, lifeforms evolved primitive microlenses long before this paper. Cyanobacteria focus incoming light on their cell membranes to locate the sun’s position; they’re probably the world’s smallest and oldest camera eyes. Other cells, like yeast and red blood cells, also naturally behave as microlenses.

What’s new about this paper is that the silica coating majorly improves the cells’ ability to focus light. More importantly, the work shows that we can tune a living organism’s optical properties through genetic engineering.

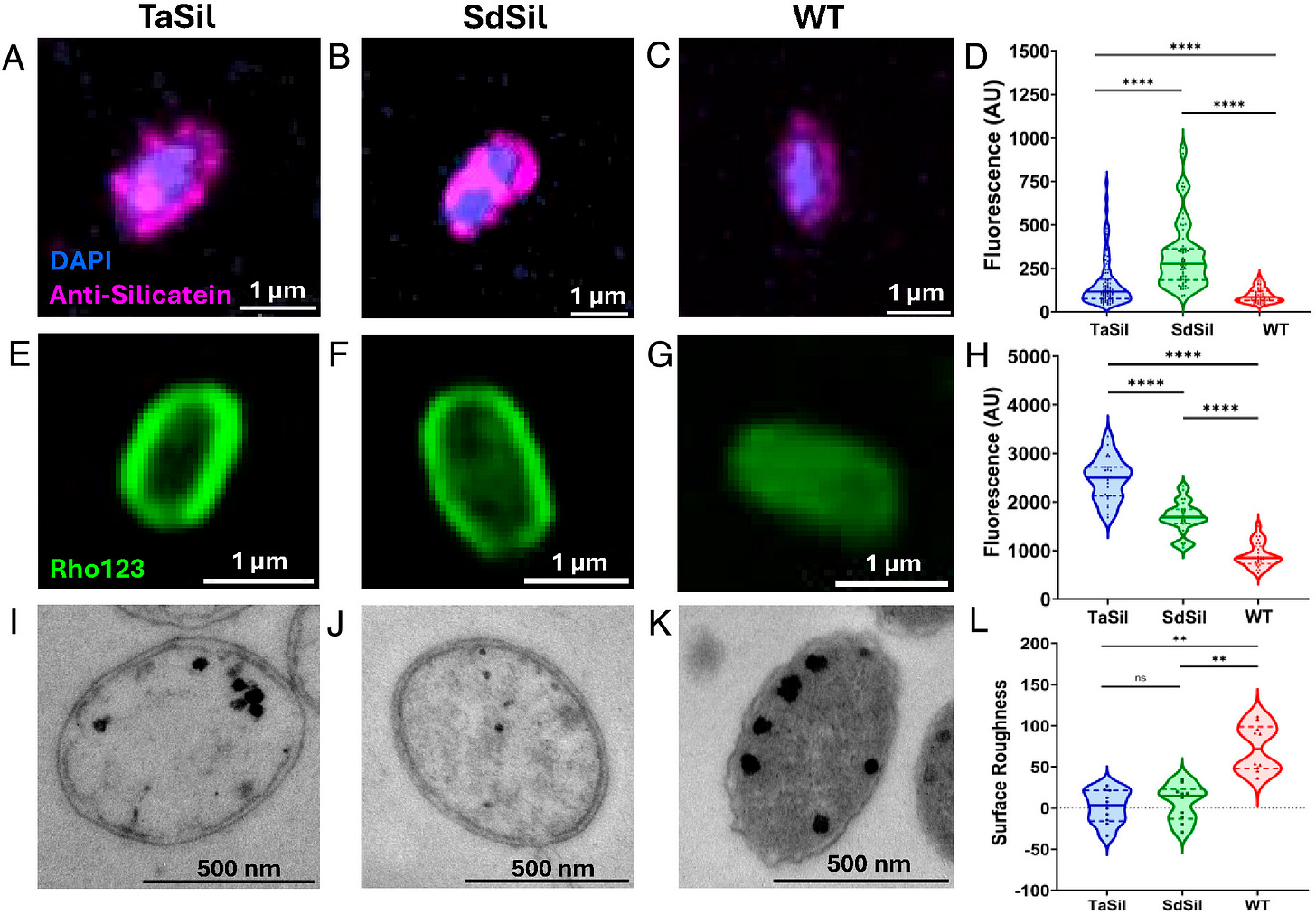

The researchers took silicatein, an enzyme from sea sponges, and fused it to OmpA, an outer-membrane protein that allows molecules to flow in and out of the cell. Silicatein grabs silicon-containing molecules from the environment and stitches them into silica polymers; sea sponges use it to build “bioglass” structures. When fused, OmpA embeds into the cell membrane and holds silicatein outward, like a fishing hook.

By flooding the engineered cells with orthosilicate (a silicon-containing molecule), the silicatein “hooks” grab it and stitch together a silica shell around the entire cell. The researchers confirmed this with confocal imaging and a dye that binds specifically to silica. The engineered cells ended up surrounded by dye, while normal cells remained unstained.

This silica shell significantly changes the cells’ optical properties. To visualize this, the researchers built a custom microscope that can shine light on cells from any imaginable angle relative to the vertical axis. Uncoated cells scattered some light but didn’t create a distinct focal spot beyond their surface. In contrast, silica-encapsulated microbes produced light beams that stretched for several microns, with peak intensities nearly an order of magnitude higher than wildtype cells.

I would have guessed this treatment might kill the cells — either because the silica shell blocks nutrients or because photons would roast them — but it doesn’t. Engineered cells continued scattering and focusing light even months after switching on the fusion protein. The only downside is that the cells grow more slowly, if at all.

What could we do with these living lenses?

My first step would be to engineer cells of different shapes and dimensions. A typical E. coli measures about two microns long and one micron wide. What if we engineered more spherical cells? Or longer cells? We could create a series of living microlenses, each with unique optical properties, by tuning the silicatein protein and adjusting the cells’ physical dimensions.

(In the video below, researchers are blasting a stationary cell with light at angles ranging from -90° to 90°. There are some orientations where a nanojet appears, but it happens quickly.)

From there, the applications depend on our imaginations. We might wire living bacteria into optical devices that don’t need batteries and last for months without a power supply. Or we could build medical devices. Instead of swallowing a pill camera powered by toxic batteries, perhaps we could engineer E. coli into a camera. I’m not sure. At this stage, it’s speculation.

Practical limitations exist with current microlenses. As pixel sizes in camera sensor arrays shrink below two micrometers, placing microlenses becomes difficult. However, cells can “swim” to a specific destination and arrange themselves autonomously. In other words, arrays of bacteria could line up over a sensor — maybe using microfluidic channels — to focus and direct light into tiny pixels.

Will any of these ideas actually happen? Probably not soon. Still, when a paper broadens our “design space” in biological engineering, it’s worth paying attention. One of my first questions, upon reading something like this, is usually: “Where else could this be applied, especially in unexpected ways?”

Consider optogenetics: Ed Boyden and Karl Deisseroth discovered channelrhodopsins—light-responsive proteins—and imagined splicing them into neurons to control action potentials. That mental leap doesn’t seem so large in hindsight.

Engineered gas vesicles, similarly, are being used to improve ultrasound resolution within the body, enabling scientists to image individual cells moving through the bloodstream. I’ve written about these structures before for Asimov Press. Mikhail Shapiro got the idea for engineering gas vesicles after reading “two short paragraphs” about photosynthetic algae!

In other words, pay attention when a paper like this appears. It might plant the seeds for something exciting, even if we don’t recognize it immediately.

I'd love to see these lenses engineered into self-healing biofilms and coated onto window panes! Maybe with translucent photosynthetic bacteria than can use rain water? 🌱🧬

These microlenses can be used as SPF booster for sunscreen at it increases the path length of light providing the light more opportunities to interact with UV absorbers in susncreen .