On Bacterial Nanotubes

Are bacteria really communicating through tubes, or are they merely an artifact?

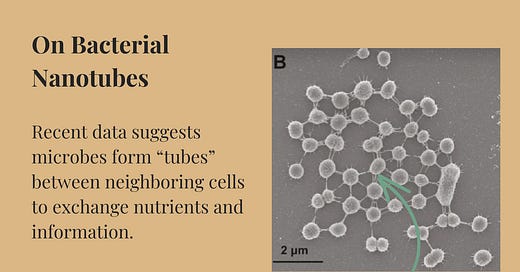

Microbes may be even more interconnected than once believed. New evidence suggests oceanic microorganisms, especially photosynthetic Prochlorococcus, build physical bridges or “nanotubes” between members of their own species and others, according to recent reporting in Quanta magazine. And because Prochlorococcus cells make something like 10 to 20 percent of Earth’s oxygen, any discovery about its behavior has some serious implications.

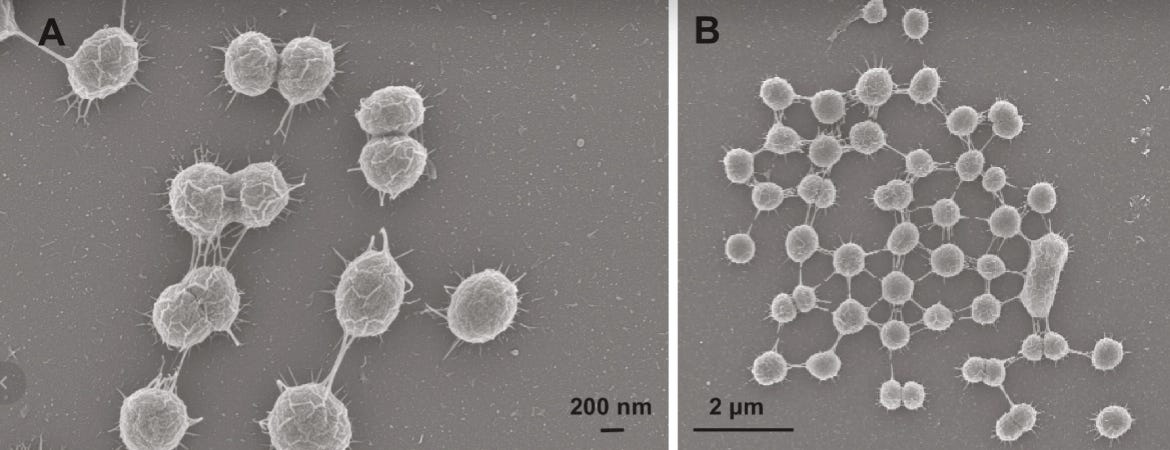

Last May, Spanish researchers reported in Science Advances that about 5 percent of Prochlorococcus cells grown in the lab formed nanotubes. They used scanning and transmission electron microscopy, fluorescence imaging, and imaging flow cytometry to back up their claims. And, importantly, they studied both dead and living cells, as well as fresh samples of seawater. In every instance, they spotted nanotubes bridging about 5 percent of cells — not only within Prochlorococcus cells, but also between different species.

“Silvery bridges linked three, four, and sometimes 10 or more cells,” according to the paper. Previous reports have described similar structures in Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis, so these nanotubes might be incredibly widespread across microbes.

The question, though, is what are these nanotubes made from? What are they doing? And are they legit or merely an artifact caused by cell death, as a 2020 study suggests?

In 2011, Israeli scientists discovered bacterial nanotubes and shared their findings in Cell. “Given the complex intercellular communication required within natural bacterial communities,” the authors wrote, “we reasoned that bacterial cells grown on a solid surface can physically interact in order to establish an effective route for exchange of molecular information.”

To test their theory, researchers mixed together B. subtilis cells carrying resistances to different types of antibiotics, then flooded the cells with a mixture of antibiotics. If cells can swap information quickly, via nanotubes, then perhaps each cell could help its neighbors survive. And that is, indeed, what they saw: B. subtilis cells swiftly formed “nanotubes” and many cells survived the antibiotic onslaught. These nanotubes, the authors argued, might represent a bacterial strategy for “extremely fast horizontal trait acquisition.”

A subsequent study pushed this claim even further. In 2015, a German group mixed together E. coli and Acinetobacter baylyi cells, engineering each organism so that it lacked — or was unable to make — a particular nutrient. They found that:

... in a well-mixed environment E. coli, but likely not A. baylyi, can connect to other bacterial cells via membrane-derived, tubular structures (hereafter referred to as ‘nanotubes’) and use these to exchange cytoplasmic constituents. Furthermore, we show that cell attachment is demand-driven and contingent on the nutritional status of auxotrophic cells…our results suggest that nanotubes can mediate the exchange of cytoplasmic nutrients among connected bacterial cells and thus help to distribute metabolic functions within microbial communities.

The same study also found that bacterial nanotubes are made from lipids. (Briefly, researchers stained the cells with a dye known to bind lipids, and it glommed on to the nanotubes.)

Despite the swelling tide of evidence, though, other groups argue that nanotubes only appear when cells experience stress — or die. In 2020, Czech researchers applied various stressors to Bacillus subtilis cells, using pressure or antibiotics, and watched nanotubes forming rapidly from only dying cells. The authors concluded:

[Nanotubes] appear to be extruded exclusively from dying cells, likely as a result of biophysical forces. Their emergence is extremely fast, occurring within seconds by cannibalizing the cell membrane…We therefore propose that bacterial nanotubes are a post mortem phenomenon involved in cell disintegration, and are unlikely to be involved in cytoplasmic content exchange between live cells.

...We used various types of stress to cause cell death (pressure, different antibiotics)…regardless of the stress applied, nanotubes were always detected associated with dying cells, though their relative amounts varied.

Obviously, there are conflicting accounts here. If the Czech authors are correct, then nanotubes are artifacts of dying cells. But that would mean some of the earlier experiments — especially the 2011 study with antibiotics — is wrong. So what gives?

Well, the Czech authors did their own experiment with antibiotics to test whether nanotubes could quickly transmit resistance genes. And it turns out that no, they can’t. “Our screen revealed that [plasmid] transfer was exclusively dependent on the cell ability to take up exogenous DNA,” the authors write, “thereby ruling out any nanotube involvement.” In other words, antibiotics kill cells and then neighboring cells quickly pick up their resistance plasmids; no nanotubes required.

I don’t know who’s right or wrong in all this, but clearly there is an amazing project here for an ambitious graduate student. I think there are several ways one could test whether these nanotubes are used by healthy cells, or merely a postmortem artifact.

I’d begin by collecting high-speed video footage. A video showing an actively dividing cell, connected to its neighbors via nanotubes, would dispel some doubts that these only form from dying cells. (After all, dead cells don’t divide.)

Another option is to track the direction and identity of cargo passing through these nanotubes. Could one artificially engineer distinct “cargo molecules” — e.g., fluorescently labeled proteins of different sizes — in a donor strain and show that they appear in a neighboring cell? If no cargo transfer is detected, that would support the hypothesis that these tubes do not function as living conduits.

In B. subtilis, nanotubes are built from cell-wall hydrolases (LytE, LytF). A PhD student could presumably clone, engineer, and express these genes in healthy cells in an effort to induce nanotube formation. They could even make large variant libraries of these proteins and try to alter the nanotubes’ lengths, diameters, and so on.

If nanotubes are legit, and if we’re able to reliably induce them in the laboratory, then that opens up all kinds of interesting applications. For starters, metabolic engineers could use these nanotubes to “divide labor” between microbial cells to increase yields. Or, one could exploit nanotubes to directly inject antibiotics or phage genes into a community of pathogens, thus skirting around biofilms. Even more ambitiously, I could imagine someone designing an entire community of specialized cells, each carrying a pared-down genome that only handles half, or a third, of its normal metabolic tasks. If nanotubes can be connected to these cells, then each cell can fill in metabolic tasks for its neighbors and share nutrients. This could, in turn, allow synthetic biologists to build more “minimal genomes” that are much easier to engineer.

Let me know how it goes, and reach out to niko@asimov.com if you’d like to talk about this.

This blog is published by Asimov, a biotechnology company building an integrated suite of cells, genes, and software for advanced genetic design.

References:

Angulo-Cánovas, E. et al. “Direct interaction between marine cyanobacteria mediated by nanotubes.” Science Advances (2024).

“The Ocean Teems with Networks of Interconnected Bacteria.” Quanta Magazine (2024).

Dubey G.P. & Ben-Yehuda S. “Intercellular Nanotubes Mediate Bacterial Communication.” Cell (2011).

Pande S. et al. “Metabolic cross-feeding via intercellular nanotubes among bacteria.” Nature Communications (2015).

Pospíšil J. et al. “Bacterial nanotubes as a manifestation of cell death.” Nature Communications (2020).